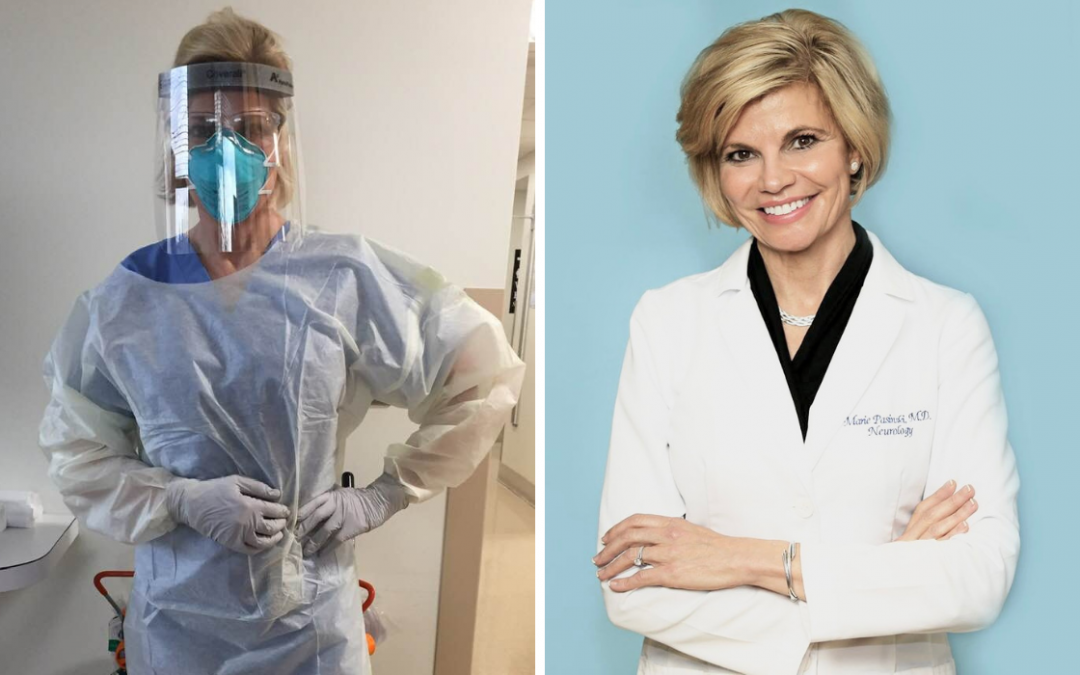

COVID-19 can affect more than just the respiratory system. We asked Assistant Professor at Harvard Medical School, MGH McCance Center for Brain Health Neurologist and WAM Advisor, Dr. Marie Pasinski, about what she’s learned from treating patients with COVID-19 and it’s impact on the brain.

WAM: Earlier this year, you were deployed into COVID duty. What was that like for you, and what did you take away from that experience?

Pasinski: Caring for COVID-19 patients has been one of the most meaningful experiences of my medical career. Last spring, as the pandemic surged in the northeast, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) experienced an overwhelming influx of patients with respiratory symptoms. Neurologists were asked to help our internal medicine colleagues care for the dramatic influx of patients. If they didn’t have enough volunteers, staff would be redeployed involuntarily.

Days earlier, one of my colleagues confided her fear of infecting her 10-month-old daughter. Our conversation triggered memories of my own stress as a young mother, juggling a career and parenting responsibilities. Since my two sons are now adults, I knew that it was my obligation to volunteer despite my own fear.

Embracing the wisdom of the renowned psychiatrist, Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross allowed me to overcome my fear. According to her teachings, “There are only two emotions: fear and love. When we’re in fear, we are not in a place of love. When we’re in a place of love, we cannot be in a place of fear.” Focusing on love enabled me to discover a new courage.

It was a privilege to be assigned to the MGH Chelsea Health Care Center, the beloved community in which I have worked for nearly 30 years. The city of Chelsea became the COVID-19 epicenter of Massachusetts due to its low income, mostly immigrant population. Multigenerational families living in overcrowded housing made quarantining virtually impossible. Combined with the large number of essential workers in Chelsea who did not have the luxury of working from home, the virus spread like wildfire. Perhaps most heart-wrenching was the pervasive fear of seeking medical attention due to increasingly harsh federal immigration measures. Many of our patients delayed coming in as long as possible, showing up with extreme shortness of breath, high fevers, and dangerously low oxygen levels.

Caring for those with memory loss and dementia was especially challenging. Imagine the terror of being sick and alone, in an unfamiliar environment, surrounded by masked faces with muffled voices. Being a non-English speaking patient further amplified their distress.

Hippocrates once said, “Wherever the art of medicine is loved, there is also a love of humanity.” Providing compassionate, expert care to our patients was a team effort powered by love. From nurses and interpreters to social workers and administrative staff– everyone pitched in with a deep sense of purpose. We experienced an indescribable camaraderie and shared humanity with each other and our patients. I am both humbled and proud to have been part of this vital effort.

WAM: You told us recently that you launched a post-COVID Brain Health Clinic at MGH. How does COVID affect the brain, and what are the most common symptoms it causes?

Pasinski: Contrary to popular belief, infection with COVID-19 is not simply limited to the lungs. It is a systemic illness that affects widespread organ systems, including the brain. Neurologic symptoms are estimated to affect anywhere from 40-60% of patients. These include headache, loss of smell/taste, weakness, numbness, dizziness, imbalance, seizures, stroke, tremors, confusion, and delirium. In addition, neuropsychiatric symptoms of profound fatigue, anxiety, and depression are also very common.

While most people with COVID-19 infection recover within a few weeks, some experience persistent symptoms. This condition is called “long COVID.” The symptoms of long COVID vary from person to person and may include any of the neurologic symptoms listed above. Long COVID is not limited to patients who have had severe illness. It also occurs in those with mild illness who did not require hospitalization.

One of the most common neurologic symptoms is brain fog. It occurs in both the young and old, affecting those who have had both mild and severe disease. Patients report impaired concentration, word-finding difficulties, and memory loss enduring months after their illness. Those with severe symptoms may be unable to return to work, live independently, or resume their normal lives. Our clinic recently evaluated a 28-year-old who could not perform her job due to short term memory loss. For those who have had mild cognitive impairment or dementia prior to COVID-19 infection, it’s not unusual to see a decline in cognition or behavioral changes. Of concern, recent research suggests that COVID-19 infection may prove to be a risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

Given the worldwide spread of COVID-19, its potentially devastating impact on brain health is daunting. Cutting-edge research is desperately needed to understand this new disease and thwart a global brain health crisis. To meet this need, MGH’s Henry and Allison McCance Center for Brain Health launched a brain health clinic for survivors of COVID-19. Our mission is to provide state of the art care and treatment for those with COVID-19 related neurologic and neuropsychiatric symptoms. In performing a multidisciplinary, comprehensive evaluation of our patients, invaluable data will be collected, enabling us to understand the mechanisms by which COVID-19 affects the nervous system. Our goal is to develop novel treatments and therapies to protect the nervous system from COVID-19 and maximize brain health.

Learn more about the McCance Center for Brain Health COVID-19 Survivor’s Clinic.

WAM: Are there things people can do to protect their neurological health in the event they develop COVID?

Pasinski: Brain health is intimately linked to physical and psychological health. Since the start of the pandemic, we all have been stressed and tested in ways we could never have imagined. During this time, we’ve been unable to engage in many of our usual go-to activities and rejuvenating self-care rituals, yet, we have never needed them more.

Below are my recommendations to maximize your physical health and cultivate well-being in the coming months:

- Stay up to date on regular medical checkups and routine screenings. Get the flu shot.

- Be kind to yourself. Accept that sometimes, just making it through the day is enough.

- Spend time outdoors and immerse yourself in nature. Studies show spending time in nature lowers cortisol levels and boosts your immune system.

- If you’re not getting enough vitamin D in your diet or sun exposure, consider taking a vitamin D3 supplement. Vitamin D deficiency has been linked to increased susceptibility to COVID-19 infection and severity.

- Get plenty of rest to bolster your immune system. If you have insomnia and common self-care remedies are unsuccessful, seek medical advice.

- Connect with others. Although we must maintain physical distance at this time, there is no barrier to how emotionally close we can bond with one another. Getting together for an outdoor chat or walk can be safely done wearing masks while keeping 6 feet apart. Keep in touch with friends and loved ones by phone, video calls, social media, letters, and email.

- If you’re feeling depressed, anxious, or overwhelmingly stressed, seek professional help. NAMI – the National Alliance on Mental Illness website offers an abundance of resources on finding treatment, online discussion groups, legal and financial assistance, and community support services. Know that the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 is available 24/7.

- Perform one act of kindness every day. It may be as simple as checking in on a neighbor or sending a thank you note to someone who’s made a difference in your life.

- Choose love over fear by repeating loving phrases throughout your day. One of my favorites is “May I be filled with loving-kindness.”

- Above all, trust that we will come through this together.